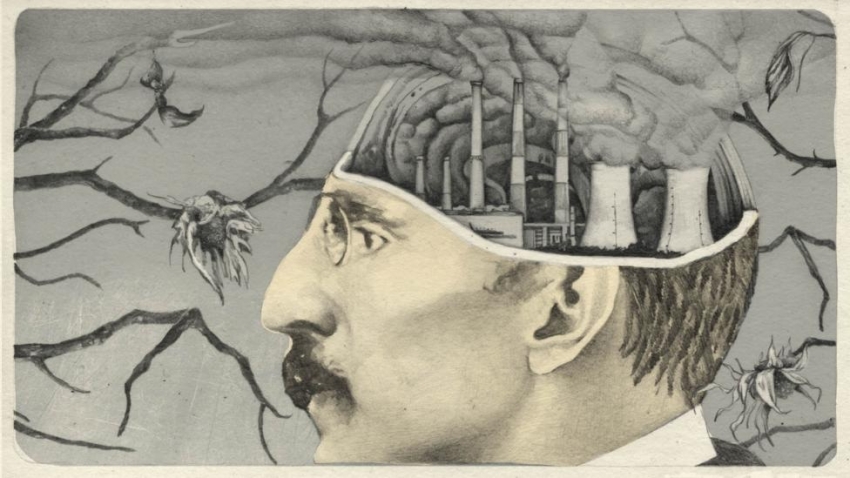

The air we breathe could be changing our behavior in ways we are only just beginning to understand. In the future, police and crime prevention units may begin to monitor the levels of pollution in their cities, and deploy resources to the areas where pollution is heaviest on a given day. This may sound like the plot of a science fiction movie, but recent findings suggest that this may well be a worthwhile act ice. Why? Emerging studies show that air pollution is linked to impaired judgment, mental health problems, poorer performance in school and most worryingly perhaps, higher levels of crime.

These findings are all the more alarming, given that more than half of the world’s population now live in urban environments – and more of us are travelling in congested areas than ever before. Staggeringly, the World Health Organization says nine out of 10 of us frequently breathe in dangerous levels of polluted air.Air pollution kills an estimated seven million people per year. But could we soon add murder figures into this too?

Watch our animated version on BBC Reel: How dirty air is polluting our minds It was in 2011 that Sefi Roth, a researcher at the London School of Economics was pondering the many effects of air pollution. He was well aware of the negative outcome on health, increased hospital admissions and also mortality. But maybe, he thought, there could be other adverse impacts on our lives. To start with, he conducted a study looking at whether air pollution had an effect on cognitive performance.

Roth and his team looked at students taking exams on different days – and also measured how much pollution was in the air on those given days. All other variables remained the same: The exams were taken by students of similar levels of education, in the same place, but over multiple days.He found that the variation in average results were staggeringly different. The most polluted days correlated with the worst test scores. On days where the air quality was cleanest, students performed better.

“We could see a clear decline [of performance] on days that were more highly polluted,” says Roth. “Even a few days before and a few days after, we found no effect – it’s really just on the day of the exam that the test score decreased significantly.”

To determine the long-term effects, Roth followed up to see what impact this had eight to 10 years later. Those who performed worst on the most polluted days were more likely to end up in a lower-ranked university and were also earning less, because the exam in question was so important for future education. “So even if it’s a short-term effect of air pollution, if it occurs in a critical phase of life it really can have a long-term effect,” he says. In 2016 another study backed up Roth’s initial findings that pollution can result in reduced productivity.

You might also like:

The air that makes you fat

How the world’s biggest cities are fighting smog

Is the world running out of fresh water?

These insights are what led to Roth’s most recent work. In 2018 research his team analysed two years of crime data from over 600 of London’s electoral wards, and found that more petty crimes occurred on the most polluted days, in both rich and poor areas.

Although we should be wary of drawing conclusions about correlations such as these, the authors have seen some evidence that there is a causal link.

Wherever the cloud of pollution travels, crime increases

As part of the same study, they compared very specific areas over time, as well as following levels of pollution over time. A cloud of polluted air, after all, can move around depending which direction the wind blows. This takes pollution to different parts of the city, at random, to both richer and poorer areas. “We just followed this cloud on a daily level and see what happened to crime in areas when the cloud arrives… We found that wherever it goes crime rate increases,” he explains.

Importantly, even moderate pollution made a difference. “We find that these large effects on crime are present at levels which are well below current regulatory standards.” In other words, levels that the US Environmental Protection Agency classifies as “good” were still strongly linked with higher crime rates.

While Roth’s data didn’t find a strong effect on the more serious crimes of murder and rape, another study from 2018 has shown a possible link. The research, led by Jackson Lu of MIT examined nine years of data and covering almost the entire US in over 9,000 cities. It found that “air pollution predicted six major categories of crime”, including manslaughter, rape, robbery, stealing cars theft and assault. The cities highest in pollution also had the highest crime rates. This was another correlational study, but it accounted for factors like population, employment levels, age and gender – and pollution was still the main predictor of increased crime levels.

Further evidence comes from a study of “delinquent behaviour” (including cheating, truancy, stealing, vandalism and substance use) in over 682 adolescents. Diana Younan, of the University of Southern California, and colleagues looked specifically at PM2.5 – tiny particles 30 times smaller than the width of a human hair – and considered the cumulative effect of exposure to these pollutants over a period of 12 years. Once again, the bad behaviour was significantly more likely in areas with greater pollution.

To check the link couldn’t simply be explained by socioeconomic status alone, Younan’s team also accounted for parental education, poverty, the quality of their neighbourhood, and many other factors, to isolate the effect of the microparticles compared to these other known influences on crime.

Younan says that her findings are especially worrying as we know that how an individual behaves during adolescence is a strong predictor of how they will behave as an adult. Delinquent individuals are more likely to perform worse at school, experience later unemployment and are more prone to substance abuse. This means that an intervention at an early age should be a priority.

Exposure to various pollutants can cause inflammation in the brain

There are many potential mechanisms that might explain how air pollution affects our morality.

Lu, for instance, has shown that the mere thought of pollution can influence our psychology through its negative associations.

Naturally, the researchers were unable to physically expose participants with pollution, so they took the next best (ethically approved) step. They showed both US and Indian participants photos of an extremely polluted city, and asked them to imagine themselves living there. “We made them psychologically experience the effects of pollution,” Lu explains. “…then asked them to really imagine living in this city, and how they would feel and how their life would be living in this environment, to make them psychologically experience air pollution versus a clean environment.”

He found that the participant’s anxiety increased, and they became more self-focussed – two responses that could increase aggressive and irresponsible behaviours. “As a self-protection mechanism we all know that when we are anxious we are more likely to punch someone in the face, than when we are calm,” says Lu. “So, by elevating peoples’ anxiety, air pollution can have a detrimental effect on behaviour.”

When we are anxious we are more likely to punch someone in the face, than when we are calm

Across further experiments, the team showed that participants in the “polluted” conditions were more likely to cheat on several tasks and overrate their performance in order to get rewards.

This research is just the start, and there could be many reasons for these effects besides the increased anxiety and self-focus that Lu describes – including physiological changes to the brain. When you breathe in polluted air, for example, it affects the amount of oxygen you have in your body at a given moment – and that in turn, can result in reduced “good air” going to your brain. It can also irritate the nose, throat, cause headaches – all of which can lower our concentration levels.

It’s also clear that exposure to various pollutants can cause inflammation in the brain and can damage brain structure and neural connections. “So what could be happening is that these air pollutants are damaging the pre-frontal lobe,” says Younan. This is the very area important for controlling our impulses, our executive function and self-control.

Besides elevating crime, that might also bring about a serious decline in mental health. A March 2019 study even showed that teenagers exposed to toxic, polluted air are at a higher risk of psychotic episodes, such as hearing voices or paranoia. Lead researcher Joanne Newbury, from King’s College London, says she cannot yet claim that her results are causal, but the findings are in line with other studies suggesting a link between air pollution and mental health. “It does add to evidence linking air pollution to physical health problems and air pollution link to dementia. If it’s bad for the body, it’s to be expected that it’s bad for the brain,” she says.

Those in the field say that there now needs to be greater awareness of the impact of pollution, along with the well-established effect on our health. “We need more studies showing the same thing in other populations and age groups,” says Younan.

Fortunately, we do have some control over just how much pollution we are exposed to day-to-day. We can be proactive and look up the air quality around us on a given day. Monitors highlight the days it is most dangerous, and when it is lowest. “If it’s dangerous I wouldn’t suggest going for a run outside, or do your work indoors,” says Younan.

While many countries are waiting for stricter legislation or government intervention to curb pollution, some places have taken positive steps. Take California, where regulation has resulted in less pollution, and interestingly, also less crime. Though promising, Younan stresses that we don’t yet know if this is coincidence or not. Meanwhile in London, from 8 April 2019 there will be a new “ultra low emission zone” which has stricter emission standards with an additional £12.50 ($16.30) daily charge for “most vehicle types” on top of the existing £11.50 congestion charge. A greater number of greener busses are also being phased in under the “cleaner air for London” initiative.

“We are doing a fairly good job in cutting pollution in many countries, but we should do more,” says Roth. “It’s not necessarily just government. But it’s also you and I. When we think about what we want to buy, how to get to places, we all affect the environment and we need to be more aware of that and make more informed decisions of what we do.”

Roth remains hopeful that rising pollution is something that is in our control to solve, but until we do we need to make people more aware of the issues.

If we all begin to monitor pollution levels ourselves, we then might start making it a habit to avoid certain activities, like outdoor sports, or even commuting on the most polluted days. Our bodies, brains, and behaviours will benefit.

---

Melissa Hogenboom is editor of BBC Reel. Her film on the same topic can be seen here, she is @melissasuzanneh on Twitter.

Did you enjoy this story? Then we have a favour to ask. Join your fellow readers and vote for us in the Webby Awards. It only takes a minute and helps support original, in-depth journalism. Thank you!

Join 900,000+ Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Linkedin

Share using Email

Open share tools

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Instagram

Sign up to our newsletter

SIMILAR ARTICLES

Conceptual pollution image (Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

The toxic killers too small to see

The effect of city life on your brain

The bittersweet story of acid rain

The dangers unleashed by melting ice

YOU'RE READING

The problem with India’s man-eating tigers

IN DEPTH

WILDLIFE

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Linkedin

Share using Email

Open share tools

SIMILAR ARTICLES

What links AI and elephants?

India has the potential to nearly quadruple the world’s tiger population. But some experts say that that could — ironically — require killing some of them.

Author image

By Rachel Nuwer in Karnataka, India

21st November 2019

B

By 11:00, Gopamma Nayaka knew something was wrong. Her husband, Hanumantha, should have returned from collecting firewood an hour before.

Gopamma sent for her son, who gathered a search party and headed to Bandipur Tiger Reserve, a nearby national park in south-western India. Just a few metres inside the forest, the group discovered Hanumantha’s half-eaten remains. The tiger that killed him was still sitting next to the body.

In the wake of her husband’s death, Gopamma struggled not only with grief but economic hardship. Her son had to drop out of university and move back home to support her. “My life was much better when my husband was alive,” she says. “My older son could have studied, but now both of my sons have to work. I feel insecure and dependent.”

Despite all this, Gopamma feels no resentment toward the tiger that killed her husband. Like many Hindus in India, she views humans as one piece of a complex web of life composed of all creatures, each with an equal right to existence. Nor is she worried that India’s tiger population is on the rise. Her husband’s death, she says, has nothing to do with the fact that the government is trying to save tigers: “This was my fate.”

Gopamma Nayaka holds the portrait of her husband Hanamuantha, accompanied by her two sons, daughter and uncle (Credit: Rachel Nuwer)

Rural Indians are unique in the world for their high tolerance for co-existing with potentially deadly wildlife. “You don’t find this in other cultures,” says Ullas Karanth, a recently retired carnivore biologist at the Wildlife Conservation Society and a leading expert on tigers. “If this kind of thing happened in Montana or Brazil, they’d wipe out everything the next day.”

You might also like:

The boys learning anti-sexism in India

Meet the women saving Africa’s wildlife

What it’s like living in California’s mountain lion county

The live-and-let-live outlook has also been foundational for India’s transformation into the world’s greatest stronghold for tigers. The country holds just 25% of total tiger habitat, but accounts for 70% of all remaining wild tigers, or around 3,000 animals today.

Success does not come without cost, however. India’s protected areas have not expanded at the same rate as its tiger population, forcing some big cats to turn to human-dominated landscapes for survival. Livestock are killed and sometimes so are people.

Attacks are relatively rare, with around 40 to 50 people annually killed by tigers – compared to around 350 people killed each year by elephants. But while getting killed by an elephant is typically viewed as something that just “happens”, like a car accident, deaths caused by tigers tap into a primordial fear that, if left unresolved, can drive communities to extremes. In many places, traditional tolerance is beginning to fray, leading to riots and targeted killing of tigers.

Not every tiger is a man-eater – not even close. No exact numbers for this behaviour exist, but Karanth guesses that only 10 to 15 of the animals become persistent predators of humans each year.

Most tigers are not man-eaters; only 10 to 15 are estimated to become persistent predators of humans each year (Credit: Getty Images)

You can’t have everybody in the countryside turning against tigers because of one animal — Ullas Karanth

When this does happen, though, the most certain way to keep the peace, Karanth and other experts believe, is to quickly dispose of man-eating tigers before they kill again. “That’s the attitude necessary if you want to have a large number of tigers,” Karanth says. “You can’t have everybody in the countryside turning against tigers because of one animal.”

This is reflected in Indian law, which states that chief wildlife wardens and senior federal officials can issue an order to shoot if it is warranted in the interest of public safety. “If a tiger is really a man-eater, we have to go after this man-eating tiger according to a very well-defined standard operating procedure,” says Anup Kumar Nayak, additional director general of India’s National Tiger Conservation Authority.

But urban animal rights groups – which hold strong political clout in India – don’t see it that way. No matter how many people a tiger has allegedly killed, many activists argue that man-eaters should be trapped and put into captivity, translocated and re-released, or simply left alone. “I feel I am the voice for the voiceless animals,” says Jerryl Banait, a physician and leading wildlife activist based in Nagpur. “You cannot inflict atrocities and injustices on animals just because they cannot express themselves.”

But none of the non-lethal measures Banait and others call for are viable ways of dealing with tigers that stalk and kill humans, Karanth says. Tiger conflicts quickly metastasise into “political football”, he continues, and while the government waffles under competing pressures, man-eaters go on killing. Local people often eventually enact their own solution, poaching not just the tiger in question, but targeting all the tigers in their area. They begin to view India’s forest department as the enemy – and conservation as something opposed to their best interests.

Under this scenario, at best, tiger numbers will stagnate. At worst, widespread revenge killings will cause the species to all but disappear.

For India to continue to shine as a tiger success story, Karanth says, it needs to come to terms with the fact that what’s best for a species does not always align with what’s best for an individual animal – especially an individual that has taken human lives. In other words, the future of the world’s tigers largely depends on convincing Indians to accept that man-eating predators must die in order for the species to thrive. “There’s no other way,” he says.

Price of success

No one knows how many tigers once roamed India’s diverse landscapes, but the cats certainly numbered in the tens, if not hundreds, of thousands. Their decline began centuries ago, with the arrival of shotguns and steel traps. Tigers were targeted for sport by the rich and for bounties by the poor, with one historian tallying over 80,000 of the big cats killed from 1875 to 1925. Hunting also wiped out tigers’ prey, causing the species to be doubly impacted.

King George V poses with the day’s kills during his tour of India in 1912; from 1875 to 1925, more than 80,000 tigers were killed (Credit: Getty Images)

By the mid-20th Century, India had lost its Asiatic cheetah and nearly all its Asiatic lions to overhunting. Its tigers would have likely disappeared as well were it not for Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who outlawed all hunting in 1971. Sometimes referred to as “India’s greatest wildlife saviour”, Gandhi strengthened wildlife legislation, set up protected areas and created a tiger task force.

“This was happening around the time of Rachel Carson and similar environmental movements in Europe – and the same wave came to India,” says Krithi Karanth, chief conservation scientist at the Centre for Wildlife Studies, a non-profit organisation in Bangalore, and Ullas Karanth’s daughter. “People started waking up to the fact that nature’s in trouble and that we can’t continue business as usual.”

Prime Minister Indira Gandhi addresses a rally in 1971, the same year she outlawed all hunting in India (Credit: Getty Images)

Tigers disappeared from 67% of India over a 100-year period

But tigers didn’t immediately rebound. In the 1980s, when Ullas Karanth, now 70, made the switch from a career in engineering to one in conservation, roughly 2,500 tigers still roamed the landscape. Ullas, who has always had a fondness for large predators, decided to focus his career on recovering his country’s tiger population. Figuring out how many tigers India had left was a first step. In 1991, he developed a novel, accurate counting method by using camera traps to identify individual tigers’ unique stripe patterns. He was puzzled, however, when he found that tiger densities varied wildly, from fewer than one to up to 15 tigers per 100 square kilometers.

Ullas suspected that low prey densities due to bushmeat poaching could be behind this – and his hunch proved correct. He eventually confirmed that a single tiger kills around 50 prey animals each year, meaning it needs a population of at least 500 prey animals to sustain it. Based on an extensive review of old hunting journals, taxidermy notes and land tenure records, Krithi later estimated that tigers disappeared from 67% of India over a 100-year period, and that many of their prey species, including deer and gaur (the world’s largest bovid), likewise declined. “The only species that doesn’t seem to be in trouble are wild pigs,” Krithi says. India’s tiger populations, in other words, are held back by the fact that there’s not enough to eat.

You might also like:

• How do you bring wildlife back to the city?

• The animals thriving in the Anthropocene

• How reintroducing wolves helped save a famous park

A tiger calls her cubs to mealtime after successfully hunting a deer; a single tiger kills around 50 animals a year for food (Credit: Getty Images)

Starting in the 1990s, Ullas began pushing for science-based tiger management with a special emphasis on conservation of prey species. He collaborated with others to facilitate the voluntary, government-funded relocation of villages situated within protected areas. When tiger poaching began to surge as a result of growing Chinese demand for the predators’ parts, Ullas’s counting method revealed the severity of the problem, and he worked with officials to develop effective anti-poaching programs.

As a result of these and other efforts, tiger populations began to grow. The greater Malenad landscape in southwestern India, for example – which includes Bandipur Tiger Reserve, where Gopamma’s husband was killed – is now home to 400 tigers, more than four times as many as when Ullas began working there 25 years ago.

As the predator’s numbers climb, however, conflicts become inevitable. Competition and territoriality force certain tigers to leave protected areas, especially youngsters seeking to establish their own territories and injured or old animals desperate for food. Most tigers in this situation prey on livestock, but a few wind up killing people as well.

“Tigers are normally terrified of humans,” Ullas says. “But when they discover the vulnerability of people, they suddenly lose that fear and realize these big, tailless monkeys are so easy to catch.”

Killing endangered species sounds counterintuitive, but in the case of habitual man-eaters, Ullas and others believe it is the only option for ensuring conservation of tigers as a species. Like pruning a tree with dead branches, the loss of a few problematic individuals has no negative impact on the whole, they say. Healthy tiger populations experience annual mortalities of 15-20% anyway, and with reproduction rates similar to house cats, deaths are quickly replaced by new births. Because man-eaters are relatively rare, under this system, only a couple dozen or so tigers would need to be put down each year.

Some animal activists argue, however, that there are too few tigers left in the wild to justify even one being killed. Others present their case from a moral standpoint. As one Twitter user in India wrote following the death of a man-eating tiger last year: “Congratulations people, another tiger murdered, another species closer to extinction.” Another lamented: “We live in a society where poor animals are killed instead of showing mercy by capturing them.”

Animal lovers protest tiger killings in 2018; some argue there are too few left in the wild to justify even a man-eater being killed (Credit: Getty Images)

Banait believes that tigers definitively proven to be man-eaters – and with all other options for saving them exhausted – should be killed. “Being a doctor, my first responsibility is to protect human beings,” he says. But he sets the bar high for definitively assigning the label of man-eater, such as comparative DNA analyses attributing multiple kills to a particular animal (a single kill, or sporadic kills, he says, could be the result of accidental, chance encounters, not intentional predation). Ullas points out, though, that gathering DNA evidence requires a level of skill that often does not exist in the countryside, and that other forensic and ecological evidence can suffice for pinning kills to a particular tiger. Ultimately, Ullas says, public safety must come first: “This is not some OJ Simpson trial, where the tiger must be assumed to be innocent until proven guilty.”

If the government does not provide a timely solution, however, local people will devise their own. They may poison all tigers in their area, or they may trap the cats and beat them to death. According to Jose Louies, chief of the wildlife crime control division at the Wildlife Trust of India, professional poachers also take advantage of such situations. Tiger bones, claws, teeth, penises and fur destined for China fetch high prices on the black market, so poachers are happy to take care of problem animals for rural Indians.

“Those who lose cattle to tigers, they’ll definitely employ poachers,” Louies says. “Poachers may also pay money to people to keep silent and allow them to take care of the problem and make a profit.”

In the worst cases, tiger incidents become release valves for years of economic and social frustrations. Communities turn against conservation efforts and violent mobs form, sometimes incited by timber poachers or other wildlife criminals who hope to weaken the forest department. “I fear mobs more than tigers,” says AT Poovaihah, a deputy conservator of forests who once ended up in hospital after an encounter with a mob. “It’s all men, some of whom are drunk, and all of whom are angry. They know we’re doing something to capture the animal, but even then, they still want to charge us.”

Some fear that the work of conservation programmes like the Kids for Tigers campaign might be undone if man-eating tigers aren’t stopped (Credit: Getty Images)

In 2013, for example, Shivamallappa Basappa, a farmer in south-western India, was killed and partially eaten by a tiger while grazing his cows on the edge of Bandipur Tiger Reserve Karnataka State. He was the third tiger victim in the span of just two weeks, and many people had reached their breaking point. A mob of some 200 men quickly formed. By the time reinforcements arrived at 01:00, the crowd had burned down the local forest department’s headquarters and set fire to a government jeep.

“We have lived in this place for 60 years, and ever since the beginning, we’ve never had a moment of peace from these wild animals,” says Shanthamurthy Devappa, a relative of Basappa’s, who says he did not take part in the violence himself. “We’ve continually been harassed and bothered by wildlife, and we got angry for that reason. It was the accumulated anger of many years.”

#JusticeForAvni

Perhaps no case better epitomises the problems surrounding man-eaters than the story of T-1, a headline-making tigress shot in November 2018 after a two-year killing spree. By the time T1’s dramatic story finally ended, at least 13 people had lost their lives and thousands of others had been terrorised.

An image of T-1, also called Avni, is held up by protestors seeking to save her from being killed (Credit: Getty Images)

In 2015, T-1 began turning up on camera traps in Pandarkhawa in Maharashtra State, a gently undulating landscape of pastures, agricultural fields and forest patches in central India. She preyed on livestock, and soon made her first human kill, a 60-year-old woman found dead in her field with deep slashes in her back. Three months later, T-1 killed a man – and then another the very next day.

Fearing blowback in India’s cities, the region’s chief wildlife warden issued an order to capture T-1, but not to kill her. India is home to a growing, powerful animal rights movement, “an extreme version of Western animal welfarism superimposed on the Hindu ethos”, as Ullas characterises it. The movement emerged in the 1990s amidst increasing wealth in urban areas, when “300 million people suddenly had more time to think of things other than just making a living”, Ullas says.

Banait – whose love of wildlife was instilled during childhood visits to the countryside with his physician parents – classifies the movement differently: “We are trying our level best to try and put our voices forward to the government so they listen to us. They should provide animals with more safety and with more dignity.”

Even if authorities do manage to capture a man-eating tiger alive, they then face the question of what to do with it. Relocating it to a different forest only moves the problem. In 2014, for example, officials and amateur naturalists captured a young man-eater near Bhadra Tiger Reserve and released him – against Ullas’s advice – in a forest some 280km (174 miles) away. Three weeks later, following a streak of livestock attacks, the tiger killed a pregnant woman.

As for keeping captured tigers in captivity, India’s zoos are full and other facilities are lacking – and all promise a dismal existence for a once-wild predator. “Any person who knows wildlife and these creatures knows it’s such a sad thing to see them in captivity,” says Poonam H. Dhanwatey, co-founder of the Tiger Research and Conservation Trust, a non-profit organisation in Maharashtra. “What’s the quality of life you’re giving them, and is it fair to put them in small cages once you remove them from freedom?”

Some biologists argue that putting a grown tiger like T-1 in captivity is no solution (Credit: Getty Images)

T-1, however, seemed especially savvy at avoiding capture. She ignored baited traps and evaded search parties deployed into the forest to catch her. After she made her seventh kill – a 20-year-old man – communities’ trust in the government was broken, their patience exhausted. People barred officials from entering their villages or even examining victims’ bodies, and a mob beat up several forest guards.

Violence would have likely escalated from there were it not for the efforts of Abharna Maheshwaram, a deputy conservator of forests in the Maharashtra Forest Department. She had a hunch that female officers would be better at keeping the peace than male ones, so she sent 18 of her female colleagues to affected villages wearing civilian clothes. They only revealed their identity as forest guards after earning the trust of the local women. The strategy worked: communities’ faith in the forest department was restored and they once again began cooperating with officials.

“One thing I learned from T-1 is that whenever there is a human-animal conflict, it is not only about the animal, it’s also all about the community with whom you’re working,” Abharna says. “I personally believe that involving communities is the solution for conservation in the country.”

Gains on the local level were hampered, however, by the ongoing legal, political and social battle that was waging across India’s cities over T-1’s fate. In February 2018 – with nine victims now attributed to the man-eating tiger – the Bombay High Court stayed an order to shoot T-1. Efforts to capture her, including through use of thermal drones, hunting dogs and a paraglider, became increasingly desperate. T-1, meanwhile, became a mother, and her two cubs began joining her on human hunts.

In August, T-1 claimed three human lives in the span of just 24 days. When the government issued a new order to capture her and her cubs and, failing that, to shoot her, Banait sought an intervention through India’s Supreme Court. “When you’re giving capital punishment – shoot-on-sight for an animal – there needs to be proper legal justification for these actions,” Banait says.

T-1, who killed at least 13 people and was killed in November 2018, is brought into a post-mortem room at the Gorewada Rescue Centre (Credit: Getty Images)

The ongoing chaos, Ullas says, also contributed to the government’s decision to permit Shafath Ali Khan, a private freelance hunter, to take part in T-1’s capture. Khan’s son, Asghar Ali Khan, who was not permitted to join the hunt, also came along. The Khans are among a dozen wealthy, self-described maharaja who have made careers out of offering sharp-shooting services for high-profile problem animals, Ullas says, but their widely publicised involvement in governmental hunts fuels the flames of outrage among animal welfare advocates and undermines local officials’ authority. “We have 80,000 forest guards, quite a few of whom are excellent marksmen,” he says. “There is absolutely no need for these glory-seeking guys.”

On November 2, Khan’s son, Asghar, was finishing dinner when he received a call reporting a tiger sighting on a nearby road. Without informing his father’s government counterparts, he and several colleagues grabbed their guns and headed out. From their vehicle they soon spotted T-1, identifiable by a tell-tale “trident” marking on her side. According to Asghar’s widely reported account, one of his colleagues shot the tiger with a tranquiliser dart, causing the enraged cat to charge. Asghar – allegedly in self-defence, but sitting within his vehicle – fired on T-1 with a rifle. She died almost instantly.

“The hunter always wanted to kill her, and he disrupted the entire operations,” Banait says. “The process in which they killed Avni was very out of the box, with many irregularities and violations of the law.”

T-1’s death sparked very different reactions. In Maharashtra, villagers celebrated with firecrackers; in cities, protestors held candlelight vigils. Maneka Gandhi, a politician, animal rights activist and widow of Indira Gandhi’s son, tweeted to her 200,000 followers that Avni had been “brutally murdered” and that her killing was “patently illegal”. She tagged her posts with the widely trending #JusticeForAvni (Gandhi declined an interview request for this story).

Protestors held candlelight vigils for the tiger T-1, also known as Avni (Credit: Getty Images)

Advocates soon began accusing the Khans of tampering with evidence and questioned whether T-1 had in fact charged the car – an aberrant behavior for a tiger, which usually reacts to a dart as it would something as minor a bee sting. Forensic analysis of the tiger’s wounds later confirmed that she had been shot from the side, likely while crossing the road and certainly not while charging. The tranquilising dart recovered from her thigh also appeared to have been put in place after she was killed. Ultimately, no-one was punished.

T-1’s story made headlines around the world, but as Ullas points out, India has had many tiger cases that are “similarly absurd, similarly comic and similarly tragic”. The entire fiasco and many of the lives it cost could have been avoided, he says, if the government had simply given the order to shoot to begin with.

From 3,000 to 15,000

Eliminating man-eaters is the most important factor for retaining social tolerance for tigers, but it’s not the only requirement. India also needs to ensure families are quickly compensated for their losses. The government mandates that tiger victims’ relatives receive 500,000 rupees (around $7,200/£5,580) and that livestock killed by predators are reimbursed as well. But this doesn’t always happen.

After Gopamma’s husband was killed, she says, the junior official she approached for help assured her she would receive compensation. “I was naive to have believed him,” she says. A higher-up official soon countered that since her husband had been trespassing in the forest when he was killed, she would not be receiving any compensatory funds after all. With no other option, she took out a loan with an exorbitant 60% annual interest rate. “I had hoped some compensation would come, but because I’m poor, I accepted my fate,” she says. “I felt totally powerless.”

Gopamma Nayaka's village Berambadi is located on the edge of Bandipur National Park and Tiger Reserve (Credit: Rachel Nuwer)

Livestock predation by tigers can also be devastating for a family making just $700 (£542) or so a year, and these impacts are much more common than human deaths. Yet in a survey of 1,370 villages in the Western Ghats, Krithi Karanth found that only 31% of people who were entitled to compensation for losses due to human-wildlife conflict were actually getting it. In interviews, she learned that people struggled with confusing paperwork and that they lacked the time or means to make multiple visits the local government office to apply. Some were also deliberately denied or asked to give bribes. “There were problems with corruption in the system and with people getting the bureaucratic run-around,” Krithi says.

In 2015, Krithi and her colleagues at the Centre for Wildlife Studies launched WildSeve, a service that acts as a go-between for people impacted by animals and the government. People call WildSeve’s toll free number to report an incident. An inspector soon arrives to document the case using an open-source mobile data kit and takes care of the paperwork. WildSeve now serves half a million people in 600 villages and has filed more than 14,000 cases on their behalf. Processing time for a given claim previously averaged 277 days, but claims are now paid out within 60 days.

WildSeve delivers a host of other services as well, from providing individuals who suffer repeat livestock losses with materials to build tiger-proof sheds, to launching a wildlife education program that reached 3,000 children last year. “I’m a huge optimist,” Krithi says. “Practical interventions will go a long way to build support for wildlife.”

But Krithi’s programme, while quickly growing, is for now still confined to a small section of Karnataka. In other parts of the state and country, human-wildlife conflict continues to breed dissatisfaction. People are becoming resistant to the idea of more tigers. Krithi and her father believe there is still time to stop the social tides from changing, however, and to restore tigers to even greater heights – if only India decides to truly make the species a priority.

Based on the results of government surveys, Ullas calculates that tigers occupy just 10 to 15% of India’s 300,000 square kilometres of currently available potential habitat, and over the past 20 years, their numbers have plateaued at about 3,000 individuals. This population trajectory runs contrary to a July press release, in which India’s government claimed that the country’s tiger population has increased by 6% annually since 2006. “In spite of the challenges India faces as a developing country, we have done a wonderful job,” says Nayak at the National Tiger Conservation Authority. “It’s been a steady increase since 2006.”

Tigers occupy just 10 to 15% of India’s 300,000 square kilometres of currently available potential habitat (Credit: Getty Images)

Ullas, however, calls the methodology behind the findings “deeply flawed”, and adds that the government has prevented any outside scientific review of its data and analyses for the past 15 years. A paper published in November 2019 in Conservation Science and Practice also concludes that India’s tiger monitoring program is “unreliable”, suffers from “a lack of transparency” and that its results are “not backed by reliable scientific evidence”.

Nayak counters that the methods are sound, and that “a lot of people have been engaged in this process”, including three outside experts from the US, UK and Australia “who have already examined all the aspects and said that yes, we’ve been doing a wonderful job”.

James Nichols, an emeritus scientist at the United States Geological Survey who specialises in animal population dynamics and management, and who collaborated with Ullas for 25 years to develop tiger sampling methods, agrees that the raw data and methodological details that the government used to arrive at its findings “should be published somewhere to permit scrutiny by methodological experts”.

So while “India has done far more and far better with tigers than any other country”, Ullas says, he believes the picture on the ground is less rosy than politicians would lead the public to believe. “We’ve yet to achieve our full potential.”

India, he continues, is at a cross-road. It can resign itself to a small, limited number of big cats, or it can become one of the world’s most stunning conservation success stories by allowing its tiger population to grow to 10,000 or even 15,000 animals. The country has the money needed to realise this dream, and as ever more people choose to move from the countryside into cities, it also has the space.

For now, however, this is not a governmental goal. “I think the [tiger] numbers can increase, but to what extent is very difficult to say at this time,” Nayak says. “We have 2,900 tigers – and increasing – but we still have a lot of difficulties with tigers straying into human-dominated landscapes in certain parts of India and creating a lot of problems.”

India is one of the world’s most biologically diverse nations, but it sets aside less than 5% of its land for wildlife – compared to the 15% set aside by the US and China. Prakash Javadekar, India’s minister of environment, forest and climate change, did not respond to interview requests for this story.

Ullas questions whether the government has the political will to step up its conservation commitments. But while discouraging, he points to India’s past as proof that things can quickly and unexpectedly change for the good.

“I could have never predicted in the 1970s, when I saw the last tigers shot and paraded, that India would once again have wild tigers,” he says. “These things come in stages. Suddenly something will change, and when it does, we have so many things going in our favour.”

--

Reporting for this story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “The Essential List”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Linkedin

Share using Email

Open share tools

Like us on Facebook

Follow us on Twitter

Follow us on Instagram

Sign up to our newsletter

SIMILAR ARTICLES

What links AI and elephants?

YOU'RE READING

How do we measure language fluency?

IN DEPTH

LANGUAGE

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Linkedin

Share using Email

Open share tools

SIMILAR ARTICLES

The words to get what you want

How to revive a lost language

How your language reflects your senses

10 types of people English can’t name

There are many ways of categorising someone’s linguistic skills, but the concept of fluency is hard to define.

Author image

By Eva Sandoval

4th September 2019

M

Mayor Pete Buttigieg’s youth, military record, and marital status may distinguish him from the other 2020 US Presidential Election candidates, but it’s his rumoured proficiency in seven languages that really has people talking.

This seemingly magical feat is especially impressive in predominantly monolingual countries like the United States and the United Kingdom (where, respectively, roughly 80% and 62% of the population speaks only English). But where such enviable talent creates an aura of mystique, it also inevitably arouses curiosity. When former US Senator Claire McCaskill asked Buttigieg to comment on his language-speaking ability in a 14 February instalment of MSNBC’s Morning Joe, he replied: “it depends what you mean by speak!” and added that he can “still kind of read a newspaper in Norwegian… but only slowly” and that he has gotten “rusty” in his Arabic and Dari. That shows humility, but not so much that Buttigieg and his camp definitively dismiss the polyglot rumours.

This is not to deride Mayor Buttigieg. His perceived fluency interests me because I’m a former language teacher – having taught English for 11 years in Japan and Italy – and I am also a Cambridge English exam speaking examiner; a role which requires me to dissect variables in candidates’ second language production such as pronunciation, discourse management, and grammatical range. Buttigieg is clearly fascinated by languages, willing to learn, and is brave enough to practice with native speakers on television – qualities that would have made him the star of my classroom. But – like so many of my ex-students who expected to go from “beginner” to “native” proficiency in two months – Buttigieg may have underestimated what it means to “speak” a language.

I can relate all too well to overestimating one’s own abilities. A “heritage speaker” of Italian, I’d been living in Italy for two years when I overheard a receptionist refer me to me as “that foreigner who doesn’t speak Italian”. I was confused, then gutted. That one casual sentence launched a journey that resulted in my being forced to acknowledge that while I had grown up speaking Italian at home and was fluent, I was not by any means proficient.

Pete Buttigieg can reportedly speak Norwegian, Spanish, Italian, Maltese, Arabic, Dari, and French (Credit: Getty Images)

What does the word “fluent” actually mean? In lay circles, this term has come to equal "native-level proficient", with no grey area between the bumbling beginner and the mellifluous master. An outsider overhearing a conversation in a foreign language only hears a fog of sounds, thus perceiving anyone who can cobble together a sentence as “fluent”.

But Daniel Morgan, head of learning development at the Shenker Institutes of English – a popular chain of English schools in Italy – says that fluency actually refers to how “smoothly” and “efficiently” a second language (L2) speaker can speak on “a range of topics in real time”. While fluency may denote a degree of proficiency, it does not automatically imply accuracy – the ability to produce grammatically correct sentences – nor does it imply grammatical range.

How important are accuracy and grammatical range? That depends on the speaker’s needs. If they simply wish to converse in social settings, their focus may be solely on achieving fluency, but if the L2 is required for business or academia, accuracy and range are crucial as communications full of errors may be seen as unprofessional.

When talking a foreign language, you may be well understood by locals, even if you make lots of grammatical errors (Credit: Alamy)

These errors can include literal word-for-word translation from their native language (“I go in Spain”), and language switch (“I want eat ringo”). Bungled verb tenses, prepositions, plurals, and articles are a natural, even essential, part of the learning process.

You might also enjoy:

The man bringing languages back to life

The 10 personality traits that English cannot name

The amazing benefits of being bilingual

Many learners, however, fall into the trap of assuming that because they are understood, their speech is “perfect”. And it isn’t only the speaker who glosses over mistakes; in the Handbook of Second Language Assessment, Nivja de Jong – senior lecturer at the Leiden University Centre for Linguistics – argues that grammatical errors usually won’t prevent comprehension on the part of the listener, who is automatically able to “edit out” mistakes. In English, a sentence like “I have 17 years” is incorrect, yet one nonetheless understands that the speaker wants to say that he is 17 years old. Furthermore, friends and teachers tend to encourage L2 learners rather than discourage them, which may also contribute to inflated self-assessment.

I think of the popular memes comparing how we envision a story or scene in our head, to the way we tell it or paint it. Those first crucial years of learning a language, you may be thinking in glorious brush strokes but speaking in scribbles.

Measures of linguistic proficiency typically consider both the accuracy and the range of the language that you can use (Credit: Alamy)

So when can someone say they “speak” a language? That’s the million-dollar question. Can someone consider themselves a Spanish speaker if they’re conversational but often can’t understand native speakers because they “talk too fast”? If they use only two verb tenses and every sentence contains mistakes?

The answer may be less “yes/no” and more “how well?”

Luckily, scales for measuring spoken fluency and overall proficiency exist. “Fluency is an abstract concept, so we assign observable variables,” explains Daniel Morgan. Two of the most reliable factors are “speech rate” and “utterance length”. Speech rate can be defined as how much (effective) language you’re producing over time, for example how many syllables per minute. Utterance length is, as an average, how much you can produce between disfluencies (e.g. a pause or hesitation). You could look at accuracy as being subsumed into fluency, in terms of grammatical accuracy, lexical choice, pronunciation, and precision.”

De Jong describes the unconscious process any speaker goes through before speaking: conceptualising what to say, formulating how to say it, and, finally, articulating the appropriate sounds. All of this takes place in roughly six syllables per second. A speaker of a second language who needs to convert their thoughts into an unfamiliar language faces an even greater challenge in meeting these strict time constraints. They must also often overcome inhibition and pronunciation challenges. Accuracy may still be lacking at this stage, but make no mistake – achieving L2 fluency is a colossal feat.

The Council of Europe’s Common European Framework of References (CEFR) for Languages groups language learners into concrete proficiency levels, where fluency and accuracy are just two of many examined criteria. The CEFR – available in 40 languages – divides proficiency into six “can do” levels – A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, and C2. A corresponds to “Basic” levels, B to “Independent”, and C to “Proficient.” Observable skills include:

A1: Capabilities range include basic introductions and answering questions about personal details provided the listener speaks slowly and is willing to cooperate.

A2: Can describe in simple terms aspects of his/her past, environment and matters related to his/her immediate needs and perform routine tasks requiring basic exchanges of information.

B1: Can deal with most daily life situations in the country where the language is spoken. Can describe experiences, dreams and ambitions and give brief reasons for opinions and goals.

B2: Can understand the themes of complex texts on both concrete and abstract topics and will have achieved a degree of fluency and spontaneity, which makes interaction with native speakers possible without significant strain for either party.

C1: Can understand a wide range of longer texts and recognise subtleties and implicit meaning; producing clear, well-structured and detailed text on complex subjects, showing controlled use of organisational patterns, connectors and cohesive devices.

C2: Can understand virtually everything heard or read, expressing themselves spontaneously, very fluently and precisely, while differentiating finer shades of meaning even in highly complex situations.

Geraint Thomas, a Cambridge English speaking exam team leader, explains: “We look at things like cohesion, response rate, discourse management, and pronunciation, but each variable has sub-variables. You can break pronunciation down into stress and individual sounds.” He emphasises that the progression is gradual. “You can expect a good B2 candidate to have certain things under control; the present tense, maybe. However, they might not have their second conditional, and you’re aware that this is a progressive thing.”

What is the span of your conversational abilities? Are you equally happy talking about economics and politics? (Credit: Alamy)

Thomas adds that individual second language speakers can display different strengths: “You can get students who are very accurate but so afraid of making mistakes that their fluency suffers and others who throw themselves into something, who are quite fluent, but their language is full of mistakes.”

According to research from the University of Cambridge English Language Assessment, it takes 200 guided hours for a motivated learner to advance from one level to the next. Key word, motivated: language acquisition varies dramatically between individuals. Is the learner open to new structures? Will they build upon what they’ve already learned instead of clinging to basic “good enough” grammar? Will they commit to consistent study and practice? Bottom line: there are many steps between “The pen is on the table” and penning a perfect thesis on a piece of literature.

Proficiency scales provide an excellent gauge for assessing L2 ability, but I believe that the quickest, dirtiest fluency and accuracy “tests” are real-life situations with native speakers. How smooth and lengthy are your interactions in your L2? Do you avoid or “blank” at certain topics and situations because you don’t have the words? Do you find yourself grasping for “key words” and content yourself with understanding “the sense” rather than the entirety of the conversation? How well can you understand a film without subtitles or read a book without a dictionary? If you write an email and ask a native speaker to proofread it, how many errors will they find?

As for me, while my Italian grammatical range has improved dramatically in my nine years in Italy, as a writer I yearn for flawless, native-like accuracy and syntax. I’m not there yet, and there are many days where I despair that I never will be.

And then I remind myself that learning a second language is like entering into a marriage. You think you know your partner when you put the ring on their finger, but it’s only the beginning, and the commitment is for life. Eva Sandoval is an Italian-American writer who has been based in Italy since 2010. Her travel, food, and culture writing has appeared in The Telegraph, CNN Travel, Fodor’s Travel Guides, and HuffPo Travel as well as various luxury hotel and airline magazines.