Elimination of HIV/AIDS by 2030

HIV/AIDS is a major global public health problem having claimed over 34 million lives so far. At present, around 36.7 million people globally are affected with HIV/AIDS. Today, Sri Lanka is named as a low prevalence country for HIV/AIDS.

The challenges facing HIV/AIDS in Sri Lanka

1.) Bringing down the rate of ‘low prevalence’ to a point of near elimination

2.) Ensure all patients with HIV/AIDS have the right to universal healthcare

3.)Ensure all patients with HIV/AIDS lead a normal life in the community without being marginalised or discriminated by the local community

Magnitude of HIV/AIDS problem in SL:

Prevalence rate is 0.01 percent. First detected in Sri Lanka in 1987.

Number of deaths from HIV/AIDS so far exceeds 400.

Approximate number of people infected with AIDS living in Sri Lanka - 3,500

Currently identified and receiving treatment in STD clinics - 1,299

Number of schoolchildren under 15 affected with HIV in Sri Lanka - less than 50

(Source: National STD/AIDS Control Programme, December 2017)

Target of HIV/AIDS programme in SL:

To reduce the prevalence from 0.01 percent to the overall goal of zero percent - target to be achieved by 2030

The fast track initiative programme, the 90-90-90 needs to identify the following.

1.) Diagnose 90 percent of population infected with HIV.

2.) Treat 90 percent diagnosed with anti viral treatment.

3.) Ensure undetectable HIV in 90 percent of patients is treated with anti viral drugs.

Prevention of HIV/AIDS

1.) Sexual education of young people is mandatory regarding sexual health, sexual responsibility and the need to practice safe sex with the use of condoms.

2.) Advising youth to engage in sexual activity with one trustworthy partner only.

3.) Screening of all pregnant mothers for HIV/AIDS.

4.) Among drug addicts - avoidance of sharing needles for injecting drugs.

5.) Advise suspected cases of HIV/AIDS to avail themselves of freely accessible STD clinics in the government sector and confirm the HIV status confidentially at no cost.

6.) Protection of the baby during pregnancy from HIV infected mothers.

REDUCING ROAD ACCIDENTS

The stark reality of road traffic accidents (RTA) in 2018 was that approximately 3,000 Sri Lankans died on roads. On average, one death occurred every three hours or eight deaths occurred daily. The government spends on each death, including basic treatment, ICU care, investigations, legal workout and post-mortem, approximately Rs. one million per victim.

The WHO’s ambitious goal is to reduce the deaths from RTA by 50 percent by 2030. To ensure this, the government will have to enforce strict laws and implement them without any exception via the National Road Safety Council to ensure the country’s roads are safe for its citizens.

Analysis of fatal road traffic accidents in 2016 revealed the following information.

Total number of road traffic deaths - 2961.

This comprised 1,157 motorcyclists, 877 pedestrians, 720 motorists and 244 cyclists. These figures confirm that roads in Sri Lanka pose a serious hazard.

Consequences of road accidents

Deaths from road traffic accidents often involve the breadwinners of families at the peak of their lives. These deaths also invariably spell economic disaster for the families as all financial resources are utilised for treatment of these victims. Invariably these victims who survive from road traffic accidents are left with severe degrees of disability ranging from partial to total paralysis, totally dependent in vegetative states.

Prevention of road traffic accidents

1.) Primary prevention - Preventing road traffic accidents before it occurs. This includes education of the public, engineering and enforcement.

2.) Secondary prevention - management of injuries

3.) Tertiary prevention - disability limitation and rehabilitation

The way forward

All road users should act with civic responsibility and obey road rules at all times. They should not drink and drive or drive when they are tired and sleepy. The insurance premium should be increased for reckless driving. Other important measures are withdrawal of licence for six months for drunk driving and implementation of strict fines on dangerous driving without any exceptions.

The Sri Lanka Medical Association(SLMA) has already initiated a programme to increase public awareness of road traffic accidents and their consequences.

KEEPING SRI LANKA MALARIA FREE

Sri Lanka was certified malaria-free on September 5, 2016. This was exactly four years after the last endogenous case of malaria was detected in a soldier at a Sri Lanka Army camp in Mullaitivu. This was exactly 100 years after the British set up the first-ever malaria field station in Kurunegala in 1912. During this period, Sri Lanka was plagued by a devastating epidemic of malaria in 1935. This epidemic affected about 80 percent of the total population of Sri Lanka, which was five million at that time. The maternal mortality during the epidemic was 5,000 per 100,000 live births and the infant mortality rate was 458 per 1,000 live births.

Sri Lanka was free of malaria temporarily in 1963. However, unremitting vigilance was not maintained and malaria re-emerged in the late 60s. Minor epidemics of malaria occurred from 1970 to 1974 and from 1986 to 1988. During this period, 1986 to 1988, malaria was the leading cause of admission of patients to the government hospitals in Sri Lanka. This was the period that I worked at the Polonnaruwa Base Hospital where one-third of all admissions to the medical and paediatric wards comprised patients sick with malaria.

Patterns of malaria epidemics in SL

Elimination of Malaria

With the decline in cases to 124 in 2001 with global funds, the task of elimination of malaria began. This was achieved through

(1.) Integrated and targeted vector control (mosquito larvae) in major irrigation channels and agricultural projects; (2.) Adult vector control by targeted spraying in high-risk areas, indoor residual spraying and the use of long-lasting insecticide sprayed bed nets; and (3.) Parasite control with mobile clinics for active and passive case detection and treatment of patients at all levels.

Despite elimination of malaria in Sri Lanka, we remain receptive and vulnerable to reintroduction of malaria. Receptivity to malaria results from

(1.) The ecosystems of the country favouring a high prevalence of malaria mosquitoes due to suitable temperature and humidity; (2.) Presence of vectors in most parts of the country in irrigation projects, streams, quarry pits and water pools; and (3.) Real danger of a new vector Anopheles stephensi in the Northern Province imported from India. This vector would cause major epidemic of urban malaria if it reaches the Western Province.

Sri Lanka is vulnerable to the reintroduction of malaria due to the tremendous increase in the migrant population, with the possibility of importing the malaria parasite to Sri Lanka from other endemic countries and delay in the detection and treating these imported malaria cases.

These high-risk groups include

(1.) Sri Lankan gem traders travelling to Madagascar and Mozambique; (2.) Businessmen who travel to Asia and Africa; (3.) Pilgrims travelling to India; (4.) Sri Lankan security forces in foreign missions; (5.) Migrant workers, refugees and asylum seekers; and (6.) Tourists from malaria-endemic areas and Sri Lankans on leisure trips to South Africa.

There have been no indigenous cases of malaria since August 2012, confirming zero local transmission since then.

In 2018, there were 47 imported cases and one introduced case in a Sri Lankan who contracted malaria from an Indian worker in Moneragala.

An important message to doctors:

(1.) Always obtain a travel history of patients who present with fever

(2.) Perform blood tests repeatedly to confirm a diagnosis of malaria.

(3.) Remember thrombocytopenia is common not only in dengue but in malaria as well.

(4.) Always follow the national guidelines during treatment.

(5.) Inform all cases of malaria to the hotline, 011 7 626 626.

Take home message to patients:

If you develop fever after visiting a malaria-endemic area, please remind your doctor that it could be malaria.

FACING THE SOCIO-ECONOMIC CHALLENGES OF AGEING POPULATION

Sri Lanka has one of the fastest ageing populations in the world with 19 percent of population belonging to the elderly population group by 2030. ( See Table 1)

With the decrease in the birth rate and rising of the expectation of life and the geriatric population will need to shift the government’s healthcare allocation funds from the pediatric to the geriatric age groups. Increase in the dependency ratio and the shrinking of the working population will consequently cause a tremendous burden on the government.

Mitigating adverse effects of rising geriatric population

1.) Increase the retirement age and encourage older workers to remain longer in the labour force.

2.) Introduce phased out retirement schemes.

3.) Promote voluntary pro-social behaviour, craft and artistic work among the elderly.

4.) Provide support for independent living for the elderly.

5.) Adaptive transport, housing and rehabilitation.

6.) Prepare for management of age-related diseases such as NCDs, dementia, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, and Alzheimer’s disease.

7.) Establishment of day care centres, psychogeriatric clinics, dementia care centres etc.

People living longer and leading productive lives is the crowning achievement of our health services. It is certainly a challenge which must be properly planned and executed. Our aim should be to add life to years and not years to life and to enter the silver age, healthy and productive.

REDUCING BURDEN OF CKDU

In the history of our nation, spanning over 2500 years, agriculture and the paddy farmer have had a special bearing on our economy. It is believed that the migration of Rajarata from Anuradhapura to Polonnaruwa and subsequently to Dambadeniya resulted from the devastating effects of malaria in these kingdoms. Today, the high prevalence of CKDu in the North-Central Province (NCP) has nearly crippled this agricultural heartland, causing a steady outmigration of people and is slowly but surely destroying the agricultural-based civilisation of our country.

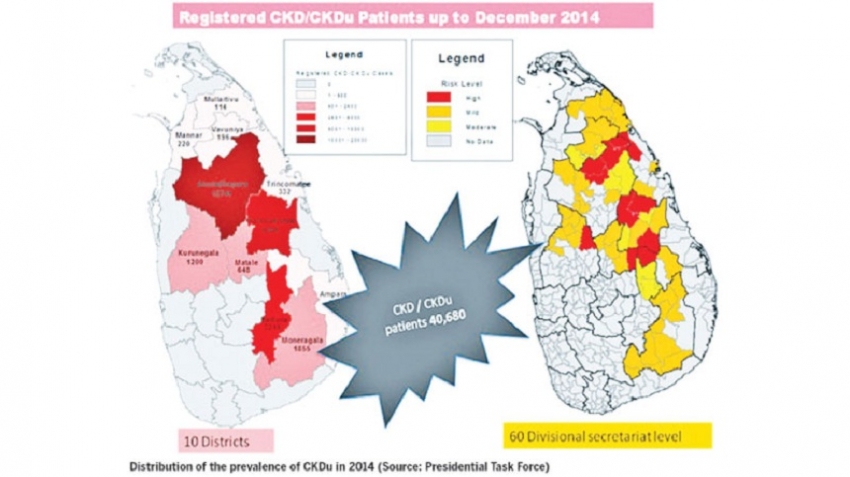

The following data highlight the stark reality of this malady.

1.) The age-standardised prevalence of CKDu is 15 percent.

2.) A population of 500,000 is at risk in the NCP – namely Medawachchiya, Padavi Sripura and Weli Oya areas

3.) Numbers severely affected with CKDu fearing death is 75,000

4.) Estimated death toll so far is 24,000

5.) Estimated daily deaths are two per day

In 2009, the following were defined as criteria for case definition of CKDu.

1.) No past history of or current treatment for diabetes, chronic hypertension, snakebite or urological disease of known aetiology or glomerulonephritis.

2.) Normal glycosylated haemoglobin (HBA1C) level is below 6.5.

3.) For blood pressure below 160 by 100 mm untreated or blood pressure below 140 by 90 mm mercury up to two hypotensive drugs used (The Health Ministry, 2019).

Main features of CKDu include an insidious onset, slowly progressive chronic interstitial nephritis which predominantly affects, poor rural male farmers in agrochemical intense form of cultivation. The heavy sun exposure in these areas leads to increased sweating. This factor, along with reduced water intake leading to dehydration further aggravate this toxic nephropathy with unique geographical distribution which appeared in Sri Lanka in the mid-1990s. CKDu has been associated strongly with the following factors.

1.) Consumption of hard water containing magnesium and calcium

2.) Spraying of glyphosate (Roundup), the most widely used herbicide in disease-endemic areas with unique metal chelating properties.

3. Use of fertilizers with heavy metals (E.g., arsenic lead, cadmium and chromium)

The above interactions result in the formation of glyphosate – metal (GM) complexes. Drinking hard water with the GM complex and subsequent absorption to the circulation leads to high levels reaching the kidney. In the kidney, high concentration of ammonium, NH4 plus ions, releases the heavy metals from the GMA lattice in the proximate tubular areas. When the lattice is broken, it releases metals such as arsenic which damage the glomeruli and leads to glomerulosclerosis and subsequent collapse while arsenic, cadmium, chromium and the other heavy metals cause proximal tubular damage leading to chronic interstitial nephritis.

All these factors associated with agriculture have resulted in change of the name of CKDu to Chronic Interstitial Nephritis of Agricultural Communities (CINAC).

(Source: Int. J. Res. Public Health 2013, Page 2137. C.N. Jayasumana et al.)

Prevention of CKDu/CINAC

1.) Fast track provision of safe water to communities living in affected areas -

Provision of reverse osmosis water purifiers at community levels in common places

(e.g., markets, community centres, temples, pradeshiya sabha grounds)

2.) Provision of safe water for schoolchildren by installing water filters in schools in the affected areas.

3.) Minimise the use of agro chemicals – herbicides and weedicides

4.) Avoid the use of chemical fertilizers

5.) Encourage farmers to engage in traditional methods of agriculture by using compost

6.) Population screening and surveillance for early detection of CINAC

It has now been proved beyond doubt that reverse osmosis by water purifiers is the only effective answer to prevent CKD/CINAC. Reverse osmosis removes all suspected causative elements of this malady (e.g., removes arsenic, cadmium, glyphosate, fluoride, calcium and magnesium) Reverse osmosis is therefore the only effective answer to prevent CINAC.

I invite all stakeholders, including the College of Nephrologists, Ceylon College of Physicians and sociologists, to form a consensus group to advise the government to control the devastation caused by CINAC in Rajarata.

This work of the task force:

(1.) Provides guidelines for case management; (2.) Provides guidelines for entry into renal replacement programme; (3.) Development of human resources - as a prerequisite to develop effective services to tackle the epidemic; (4.) Establishment of a centre for academic research at the heartland of the epidemic in Anuradhapura - the Rajarata University is the obvious choice. This centre should work closely with the renal care and research centre of the Health Ministry; and (5.) Provision of social welfare - the devastation of the farming community in the NCP as a result of the epidemic deserves a special budget to provide social and financial support.

The CINAC is a national catastrophe perhaps unparalleled in recent history. If we do not act now and do our utmost to reduce the incidence by preventing or restricting the use of agrochemicals, we will be judged by history as uncaring, insensitive and indifferent people who ignored this catastrophe while Rajarata was poisoned to extinction. These challenges could be achieved by educating medical professionals, media, public and by changing the attitude of health lawmakers.

We intend to play an advocacy role in the Health Ministry and ensure proper allocation and utilisation of health resources. We hope to conduct regular programmes for the media and the public regarding these challenges and update doctors with workshops and symposia on these topics.

History of the SLMA

Prof. Anula Wijesundara is the 122nd President of the SLMA. The SLMA is the oldest of all national professional medical associations of Asia and Australasia.

1987 - Established as the Ceylon branch of the British Medical Association.

I951 - Name changed to Ceylon Medical Association following the declaration of independence in 1948.

1972 - Renamed as the Sri Lanka Medical Association with the promulgation of the new Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka.

The SLMA was housed at the Ceylon colonial library for 73 years. Later, it was moved to the consultant’s lounge at the former General Hospital Colombo.

Since July 1964, the ‘Wijerama House’ became the home of the SLMA through the magnanimous donation of Dr. Edmund Medonza Wijerama at No. 6, Wijerama Mawatha. This donation was made during his lifetime. The first event that was carried out in the 132nd year of the SLMA was an alms giving and a pirith pinkama. This was performed as an expression of our remembrance, gratitude and to offer merit to Dr. and Mrs. E. M. Wijerama.

Working from this historic edifice since then, the SLMA has grown in strength not only in numbers but immensely in prestige serving the profession and serving the nation with honour, dignity and humility.

Objectives of SLMA

1.) Enhance capacity and advocacy for comprehensive, curative and preventative health service.

2.) Promote professionalism, good medical practice and ethical conduct.

3.) Disseminate knowledge and provide opportunities for continuous professional development.

4.) Encourage ethical medical research.

5.) Education of public on health related matters.

6.) Enhance collaboration with all professionals allied to healthcare.

7.) Provide advocacy role for health related issues.

8.) Provide assistance in times of natural disasters.

(From the corporate plan, presidency of Professor Lalitha Mendis, 2009)