UN Secretary General António Guterres said countries in the region were among the most vulnerable to global warming and should be on the "front line" of efforts to stop it.He cited a new study that found that Asian countries were at particular risk of climate-driven flooding.Coal is a major source of power in many Asian countries.Speaking to reporters in the Thai capital Bangkok on Saturday, Mr Guterres described climate change as the "defining issue of our time".The UN chief referenced a study published on Tuesday, which found that climate change would put millions more people at risk from coastal flooding by 2050 than previously thought.The majority of those implicated were in developing countries across Asia, the study said.

Mr Gutterres said that while "people can discuss the accuracy of these figures...what is clear is that the trend is there".He said the issue was "particularly sensitive" in Asia, where a "meaningful number" of new coal power plants are planned."We have to put a price on carbon. We need to stop subsidies for fossil fuels. And we need to stop the creation of new power plants based on coal in the future," Mr Gutterres warned.

Tuesday's report by Climate Central, a US-based non-profit news organisation, said 190 million people would be living in areas that are projected to be below high-tide lines in the year 2100.It found that even with moderate reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, six Asian countries (China, Bangladesh, India, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Thailand), where 237 million people live today, could face annual coastal flooding threats by 2050.

China - 93 million people

Bangladesh - 42 million

India - 36 million

Vietnam - 31 million

Indonesia - 23 million

Thailand - 12 million

12 years to save the planet? Make that 18 months

Do you remember the good old days when we had "12 years to save the planet"?Now it seems, there's a growing consensus that the next 18 months will be critical in dealing with the global heating crisis, among other environmental challenges.Last year, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reported that to keep the rise in global temperatures below 1.5C this century, emissions of carbon dioxide would have to be cut by 45% by 2030.

But today, observers recognise that the decisive, political steps to enable the cuts in carbon to take place will have to happen before the end of next year.The idea that 2020 is a firm deadline was eloquently addressed by one of the world's top climate scientists, speaking back in 2017.

"The climate math is brutally clear: While the world can't be healed within the next few years, it may be fatally wounded by negligence until 2020," said Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, founder and now director emeritus of the Potsdam Climate Institute.

The sense that the end of next year is the last chance saloon for climate change is becoming clearer all the time.

"I am firmly of the view that the next 18 months will decide our ability to keep climate change to survivable levels and to restore nature to the equilibrium we need for our survival," said Prince Charles, speaking at a reception for Commonwealth foreign ministers recently.

UK heatwave 'set to break records'

Records tumble as Europe swelters in heatwave

'No brainer' fuel change to cut transport CO2

Used cooking oil imports may boost deforestation

Government 'like Dad's Army' on climate change

So why are the next 18 months so important?

The Prince was looking ahead to a series of critical UN meetings that are due to take place between now and the end of 2020.

Ever since a global climate agreement was signed in Paris in December 2015, negotiators have been consumed with arguing about the rulebook for the pact.

But under the terms of the deal, countries have also promised to improve their carbon-cutting plans by the end of next year.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image caption

Prince Charles has stressed how important the next 12 months are in tackling climate change

One of the understated headlines in last year's IPCC report was that global emissions of carbon dioxide must peak by 2020 to keep the planet below 1.5C.

Current plans are nowhere near strong enough to keep temperatures below the so-called safe limit. Right now, we are heading towards 3C of heating by 2100 not 1.5.

As countries usually scope out their plans over five and 10 year timeframes, if the 45% carbon cut target by 2030 is to be met then the plans really need to be on the table by the end of 2020.

What are the steps?

The first major hurdle will be the special climate summit called by UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres, which will be held in New York on 23 September.

Mr Guterres has been clear that he only wants countries to come to the UN if they can make significant offers to improve their national carbon cutting plans.

This will be followed by COP25 in Santiago, Chile, where the most important achievement will likely be keeping the process moving forward.

But the really big moment will most likely be in the UK at COP26, which takes place at the end of 2020.

The UK government believes it can use the opportunity of COP26, in a post-Brexit world, to show that Britain can build the political will for progress, in the same way the French used their diplomatic muscle to make the Paris deal happen.

"If we succeed in our bid (to host COP26) then we will ensure we build on the Paris agreement and reflect the scientific evidence accumulating now that we need to go further and faster," said Environment Secretary Michael Gove, in what may have been his last major speech in the job.

"And we need at COP26 to ensure other countries are serious about their obligations and that means leading by example. Together we must take all the steps necessary to restrict global warming to at least 1.5C."

Reasons to be cheerful?

Whether it's the evidence of heatwaves, or the influence of Swedish school striker Greta Thunberg, or the rise of Extinction Rebellion, there has been a marked change in public interest in stories about climate change and a hunger for solutions that people can put in place in their own lives.

People are demanding significant action, and politicians in many countries have woken up to these changes.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image caption

The rise of school strikers like Greta Thunberg has reflected growing interest in the climate question

Ideas like the green new deal in the US, which might have seemed unfeasible a few years ago have gained real traction.

Some countries like the UK have gone even further and legislated for net zero emissions by 2050, the long-term goal that will keep temperatures down.

Prince Charles' sense that the next 18 months are critical is shared by some climate negotiators.

"Our group of small island developing states share Prince Charles's sense of the profound urgency for ambitious climate action," said ambassador Janine Felson from Belize who is the chief strategist for the Alliance of Small Island States group in the UN.

"All at once we are witness to a collective convergence of public mobilisation, worsening climatic impacts and dire scientific warnings that compel decisive climate leadership."

"Without question, 2020 is a hard deadline for that leadership to finally manifest itself."

Reasons to be fearful?

With exquisite timing, the likely UK COP in 2020 could also be the moment the US finally pulls out of the Paris agreement.

But if Donald Trump doesn't prevail in the presidential election that position could change, with a democrat victor likely to reverse the decision.

Either step could have huge consequences for the climate fight.

Right now a number of countries seem keen to slow down progress. Last December the US, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Russia blocked the IPCC special report on 1.5C from UN talks.

Just a few weeks ago in Bonn, further objections from Saudi Arabia meant it was again dropped from the UN negotiations, much to annoyance of small island states and developing nations.

Image copyrightANADOLU AGENCY

Image caption

The US and Saudi Arabia have joined forces to restrict the use of IPCC science reports in climate talks

There will be significant pressure on the host country to ensure substantial progress. But if there's ongoing political turmoil around Brexit then the government may not have the bandwidth to unpick the multiple global challenges that climate change presents.

"If we cannot use that moment to accelerate ambition we will have no chance of getting to a 1.5 or 2C limit," said Prof Michael Jacobs, from the University of Sheffield, a former climate adviser to Prime Minister Gordon Brown.

"Right now there's nothing like enough understanding of, or commitment to, this among leading countries. That's why the UN Secretary General is holding a summit in September.

"It's great that the COP might be in UK because we have a big civil society ecosystem and much higher climate awareness than in most other countries. But the movement here has barely started to think about how to apply sufficient pressure."

There's also been a strong warning shot from the UK's Committee on Climate Change (CCC).

At the launch of their review of progress made by the UK government on tackling climate change, the country was found not to be on track despite legislating for net zero emissions by 2050.

"The government must show it is serious about its legal obligations…[its] credibility really is at stake here," said CCC chief executive Chris Stark.

"There is a window over the next 12-18 months to do something about this. If we don't see that, I fear the government will be embarrassed at COP26."

And it's not all about climate change

While the decisions taken on climate change in the next year or so will be critical, there are a number of other key gatherings on the environment that will shape the nature on preserving species and protecting our oceans in the coming decades.

Earlier this year a major study on the losses being felt across the natural world as result of broader human impacts caused a huge stir among governments.

The IPBES report showed that up to one million species could be lost in coming decades.

To address this, governments will meet in China next year to try to agree a deal that will protect creatures of all types.

The Convention on Biological Diversity is the UN body tasked with putting together a plan to protect nature up to 2030.

Next year's meeting could be a "Paris agreement" moment for the natural world. If agreement is found it's likely there will be an emphasis on sustainable farming and fishing. It will urge greater protection for species and a limit on deforestation.

Next year, the UN Convention on the Laws of the Sea will also meet to negotiate a new global oceans treaty.

This has the potential to make a real difference, according to UK Environment Secretary Michael Gove.

"We have been convinced by the evidence of environmental degradation which occurs without adequate protection," he said in a speech last week.

"And that is why the United Kingdom has taken the lead in ensuring at least 30% of the ocean we are responsible for is protected by 2030 - a trebling of the present target. We will be asking all nations to sign up to that goal."

If all this comes to pass, the world might have a fighting chance of preserving our natural environment.

But the challenges are huge, the political involvement patchy.

So don't hold your breath!

UN panel signals red alert on 'Blue Planet'

By Matt McGrath

Environment correspondent, Monaco

25 September 2019

commentsShare this with Facebook Share this with Messenger Share this with Twitter Share this with Email Share

Related TopicsClimate change

Image copyrightSPL

Image caption

Coral reefs are threatened by the acidification of the oceans

Climate change is devastating our seas and frozen regions as never before, a major new United Nations report warns.

According to a UN panel of scientists, waters are rising, the ice is melting, and species are moving habitat due to human activities.

And the loss of permanently frozen lands threatens to unleash even more carbon, hastening the decline.

There is some guarded hope that the worst impacts can be avoided, with deep and immediate cuts to carbon emissions.

This is the third in a series of special reports that have been produced by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) over the past 12 months.

Email your question about the IPCC report to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Media captionA visit to the Sermilik glacier, which is rapidly melting

The scientists previously looked at how the world would cope if temperatures rose by 1.5C by the end of this century. They also reported on how the lands of the Earth would be affected by climate change.

However, this new study, looking at the impact of rising temperatures on our oceans and frozen regions, is perhaps the most worrying and depressing of the three.

What is climate change?

Global warming causing ocean 'emergency'

Thunberg to leaders: 'You've failed us on climate'

Twelve years to save Earth? Make that 18 months...

So what have they found and how bad is it?

In a nutshell, the waters are getting warmer, the world's ice is melting rapidly, and these have implications for almost every living thing on the planet.

"The blue planet is in serious danger right now, suffering many insults from many different directions and it's our fault," said Dr Jean-Pierre Gattuso, a co-ordinating lead author of the report.

Image copyrightSPL

Image caption

Low-lying small island states will be badly hit by sea level rise

The scientists are "virtually certain" that the global ocean has now warmed without pause since 1970.

The waters have soaked up more than 90% of the extra heat generated by humans over the past decades, and the rate at which it has taken up this heat has doubled since 1993.

The seas were once rising mainly due to thermal expansion - which refers to the way the volume of water expands when it is heated. The extra energy makes the water molecules move around more, causing them to take up more space. But the IPCC says rising water levels are now being driven principally by the melting of Greenland and Antarctica.

Thanks to warming, the loss of mass (which refers to the amount of ice that melts and is lost as liquid water) from the Antarctic ice sheet in the years between 2007 and 2016 tripled compared to the 10 years previously.

Greenland saw a doubling of mass loss over the same period. The report expects this to continue throughout the 21st Century and beyond.

For glaciers in areas like the tropical Andes, Central Europe and North Asia, the projections are that they will lose 80% of their ice by 2100 under a high carbon emissions scenario. This will have huge consequences for millions of people.

Image copyrightSCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Image caption

Glaciers around the world are losing their ice fast

What are the implications of all this melting ice?

All this extra water gushing down to the seas is driving up average ocean water levels around the world. That will continue over the decades to come.

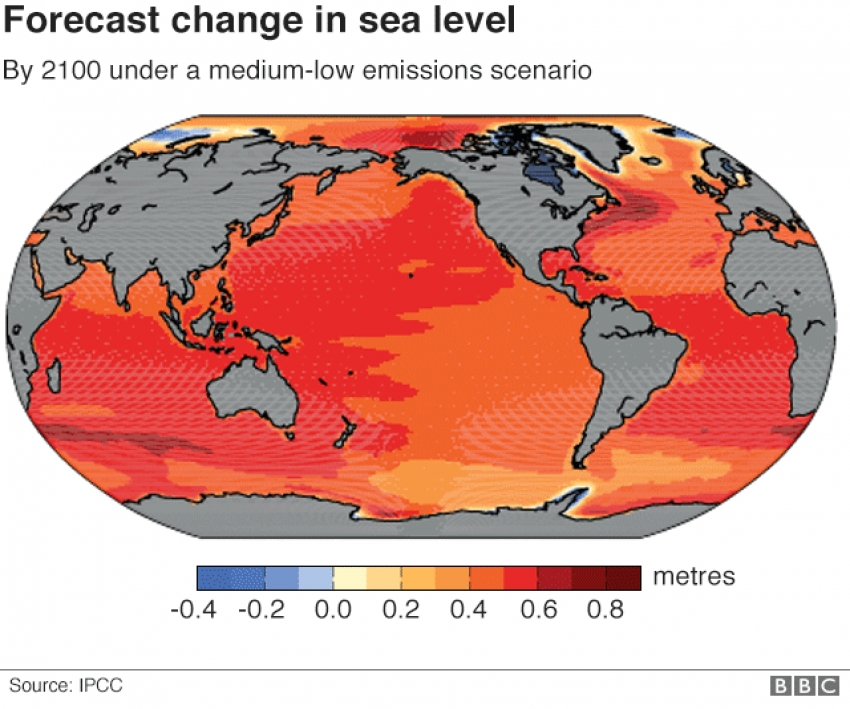

This new report says that global average sea levels could increase by up to 1.1m by 2100, in the worst warming scenario. This is a rise of 10cm on previous IPCC projections because of the larger ice loss now happening in Antarctica.

"What surprised me the most is the fact that the highest projected sea level rise has been revised upwards and it is now 1.1 metres," said Dr Jean-Pierre Gattuso, from the CNRS, France's national science agency.

"This will have widespread consequences for low lying coasts where almost 700 million people live and it is worrying."

Analysis by David Shukman - Science Editor, Hull

On the east coast of England, most of the city of Hull lies below the level of a typical high tide. The sea here can be both a source of wealth and a threat to life.

So the conclusions of the IPCC report have real meaning. A storm surge on a winter's night six years ago found a weak link in a sea wall and flooded businesses and homes.

New defences were ordered and the construction teams are now at work along the shore. But the barriers cannot protect everyone. Computer simulations, developed by the University of Hull, show that if the level of the ocean is one metre higher than now the centre of the city ought to be fine but neighbouring areas will go under.

This highlights a painful question, faced in low-lying places the world over: which should be saved and which should be abandoned as the waters rise?

Image caption

Sea level rise was once mainly due to thermal expansion of the oceans, but the melting of Greenland and Antarctica has now taken over as the principle driver

The report says clearly that some island states are likely to become uninhabitable beyond 2100.

The scientists also say that relocating people away from threatened communities is worth considering "if safe alternative localities are available".

What will these changes mean for you?

One of the key messages is the way that the warming of the oceans and cryosphere (the icy bits on land) is part of a chain of poor outcomes that will affect millions of people well into the future.

Under higher emissions scenarios, even wealthy megacities such as New York or Shanghai and large tropical agricultural deltas such as the Mekong will face high or very high risks from sea level rise.

The report says that a world with severely increased levels of warm water will in turn give rise to big increases in nasty and dangerous weather events, such as surges from tropical cyclones.

"Extreme sea level events that are historically rare (once per century in the recent past) are projected to occur frequently (at least once per year) at many locations by 2050," the study says, even if future emissions of carbon are cut significantly.

"What we are seeing now is enduring and unprecedented change," said Prof Debra Roberts, a co-chair of an IPCC working group II.

Media captionNasa visualisation of the melting Greenland ice sheet

"Even if you live in an inland part of the world, the changes in the climate system, drawn in by the very large changes in the ocean and cryosphere are going to impact the way you live your life and the opportunities for sustainable development."

The ways in which you may be affected are vast - flood damage could increase by two or three orders of magnitude. The acidification of the oceans thanks to increased levels of CO2 is threatening corals, to such an extent that even at 1.5C of warming, some 90% will disappear.

When CO2 is dissolved in water it forms carbonic acid. So, the more carbon dioxide that dissolves in our oceans, the more acidic the water gets.

Species of fish will move as ocean temperatures rise. Seafood safety could even be compromised because humans could be exposed to increased levels of mercury and persistent organic pollutants in marine plants and animals. These pollutants are released from the same fossil fuel burning that release the climate warming gas CO2.

Even our ability to generate electricity will be impaired as warming melts the glaciers, altering the availability of water for hydropower.

Image copyrightGETTY IMAGES

Image caption

The melting of permafrost could add billions of tonnes of CO2 to the atmosphere

Permafrost not so permanent

Huge amounts of carbon are stored in the permanently frozen regions of the world such as in Siberia and Northern Canada.

These are likely to change dramatically, with around 70% of the near surface permafrost set to thaw if emissions continue to rise.

The big worry is that this could free up "tens to hundreds of billions of tonnes" of CO2 and methane to the atmosphere by 2100. This would be a significant limitation on our ability to limit global warming in the centuries to come.

So what happens in the long term?

That's a key question and much depends on what we do in the near term to limit emissions.

However, there are some warnings in the report that some changes may not be easily undone. Data from Antarctica suggests the onset of "irreversible ice sheet instability" which could see sea level rise by several metres within centuries.

Image copyrightSPL

Image caption

Climate change might force species to move their ranges

"We give this sea level rise information to 2300, and the reason for that is that there is a lot of change locked in, to the ice sheets and the contribution that will have to sea level rise," said Dr Nerilie Abram from the Australian National University in Canberra, who's a contributing lead author on the report.

"So even in a scenario where we can reduce greenhouse gases, there are still future sea level rise that people will have to plan for."

There may also be significant and irreversible loses of cultural knowledge through the fact that the fish species that indigenous communities rely on may move to escape warming.

Does the report offer some guarded hope?

Definitely. The report makes a strong play of the fact that the future of our oceans is still in our hands.

The formula is well worn at this stage - deep, rapid cuts in carbon emissions in line with the IPCC report last year that required 45% reductions by 2030.

"If we reduce emissions sharply, consequences for people and their livelihoods will still be challenging, but potentially more manageable for those who are most vulnerable," said Hoesung Lee, chair of the IPCC.

Indeed, some of the scientists involved in the report believe that public pressure on politicians is a crucial part of increasing ambition.

"After the demonstrations of young people last week, I think they are the best chance for us,," said Dr Jean-Pierre Gattuso.

"They are dynamic, they are active I am hopeful they will continue their actions and they will make society change."